eulogy

september 2024 (photographs & handwritten experiments)

My grandfather died in February. I didn’t start writing the eulogy until this week — the funeral is tomorrow. It’s been on my to-do list for months now.

I can’t explain why it took me so long to write without, I guess, articulating the forgetful strain of grief that I’ve been hit with. For context: Ye-ye has been dying for years. Every time we got a phone call from my aunt in Illinois telling us that this is it, I released a different part of him from my mind. Some were more tangible, of course, like his loss of English and eventually (after the second stroke) his loss of speech altogether. Other parts are stranger and more nebulous. For instance, his meanness is something that I perversely grieved at one point, his ability to make you feel mildly like shit about yourself for your white-washed ass not knowing enough Chinese or not having enough career ambition when he had to fight tooth and nail to immigrate. He could never understand why “you people are so [insert entitled American attribute here].” When he became gentle and totally dependent in his final years, I grieved the part of him that could take me down a notch in a way no one else could.

What I mean to say is that every near-death of his has resulted in incremental oblivion for me. As I have lost more of him, I’ve let go of more memories too. In those later phases of knowing him, the last thing I wanted to do was remember how he used to be, and so I didn’t. When he died, I was more relieved than sad, which made me feel inhumane. Even now, I haven’t cried about it at all, because I can’t remember much.

How do you write a eulogy for someone you’ve been forgetting for years?

The eulogy, as observed

I’m typing this in the back seat of the car right now, driving from Indianapolis to Bloomington, IL, where the funeral will be held. It’s been awhile since we’ve been back to the Midwest, since before my dad got sick, and it hit me just then that (in an obvious way) this is the first time we’re visiting that Ye-ye won’t be there. Ye-ye only ever had memories of my dad in good health; I am perversely glad for this.

I decided that because the eulogy is ultimately a form of public writing, one of the most immediate and ubiquitous forms in fact, I would motivate myself to finish writing it by addressing this (semi) public audience here and dwelling in the writing process a little.

A good eulogy is a difficult thing to write. It requires balancing a number of unpredictable factors: speaking to a mixed audience (most of whom know the person from one particular side of their life but not all others), scaling the infinity of a person’s life into an impossibly legible frame without simplifying them too much, and contending with how the fluctuations of grief affect both content and tone, first in the writing and then of course in the delivery.

Up until this point, I’ve only written one eulogy before, for my great uncle who died in Las Vegas when I was in high school. But I’ve been to many funerals throughout my life because we have such a gigantic extended family almost all of whom live in California (which means lots of weddings, funerals, and anniversaries within driving distance) and because Sam and my dad are involved at Old First Church in SF which, unfortunately, lives up to its name in demographic breakdown. My mom, in particular, values going to the funerals of people who barely touched her life — or did so only in very specific ways. I remember going with her to the funeral of Mr. Lee, our neighbor who inexplicably brought us a bag of bread every Thursday. Or the funeral of her distant cousin Ray; for some reason, we all really glommed onto a single detail that someone mentioned in their eulogy of Ray, which was that he always cleaned up the kitchen while he was in the process of cooking. I don’t know why that detail was so poignant but every time I cook with my mom, she brings it up as the “Cousin Ray method,” of washing your pots and pans and wiping the counter while you wait for things to boil.

Most recently, I went to my Aunt Jean’s funeral in Visalia in late August. Aunt Jean was my mom’s dad’s cousin’s wife. She co-owned Town and Country Market in Porterville with (as we called him) Cousin Ted. They would send us boxes of oranges every year. I can’t say I remember ever talking directly to Aunt Jean face-to-face, but we would certainly see her and Cousin Ted at various family reunions in Sacramento. She gave out magnifying glasses as party favors. I still have one; I used to keep it in an old lunch box. Her funeral took place outdoors at a Confucian temple and cultural center. There were a couple eulogies that reached for a greater totality of her life story, but when her grandchildren gave their eulogies one by one, I was struck by how most of them focused on describing recurring acts and gestures. Specific recipes of hers that they loved, the tone of her voice when she disagreed with you, things like that. I tried to take note of the simplicity and care of their descriptions when I was writing my eulogy for Ye-ye.

The greatest pitfalls of eulogy-writing, from my observations, are self-indulgence on one end and impersonal triteness on the other. In other words, it’s really not about you and therefore shouldn’t become a wandering, first-person narrative excavation of the dead. Often, self-indulgent eulogies seem motivated by guilt more than anything else; along the lines of this person did so much for me and I never appreciated them or even (more commonly and understandably among my generation) I regret the language barrier that meant I could never understand this person. But the eulogy also can’t be totally divorced from your complex feelings about the person, guilt included, because otherwise what results is a strangely impersonal bas-relief of only the easiest, most accessible, most non-negotiable aspects.

Eulogies also work as a composite. The meaning of each individual speech is inevitably put in conversation with every other speech given that day, to ask the implicit question of How was this person consistent? How did they diverge? For Aunt Jean, nearly everyone talked about her cooking, her generosity, her peanut-butter rice krispie treats, her sticky rice, the grocery store that she treated as a centerpiece of community. As each person came up to speak, it felt like they were collectively recreating the living pulse of her. But this is another unpredictable aspect of eulogy-writing. Before the day of the funeral itself, you have no real way of knowing how your singular perspective will slot into the total portrait. It does make you wonder at the randomness of how a person’s life can be narrativized at its culmination, when it is no longer up to the person themself.

The eulogy writing process

I am unaccustomed to starting with form and working toward what I really mean to say; almost invariably, I prefer to go the other way around (as much as that binary is a myth). But because I was having so much trouble even remembering Ye-ye, and because the eulogy itself is such a specific (but expansive) form, I experimented with different forms of writing to both ground myself in the act of recollection and extend beyond what I can easily regurgitate. I’ve decided to share some of them here.

I also had to urgently service my laptop this week before heading to the UK next week because its battery capacity was completely shot (I have procrastinated for far too long…). So my entire writing process took place long-form, hand-written. This was ultimately helpful. I don’t think immediate deletion and self-editing would have aided me in honest remembrance.

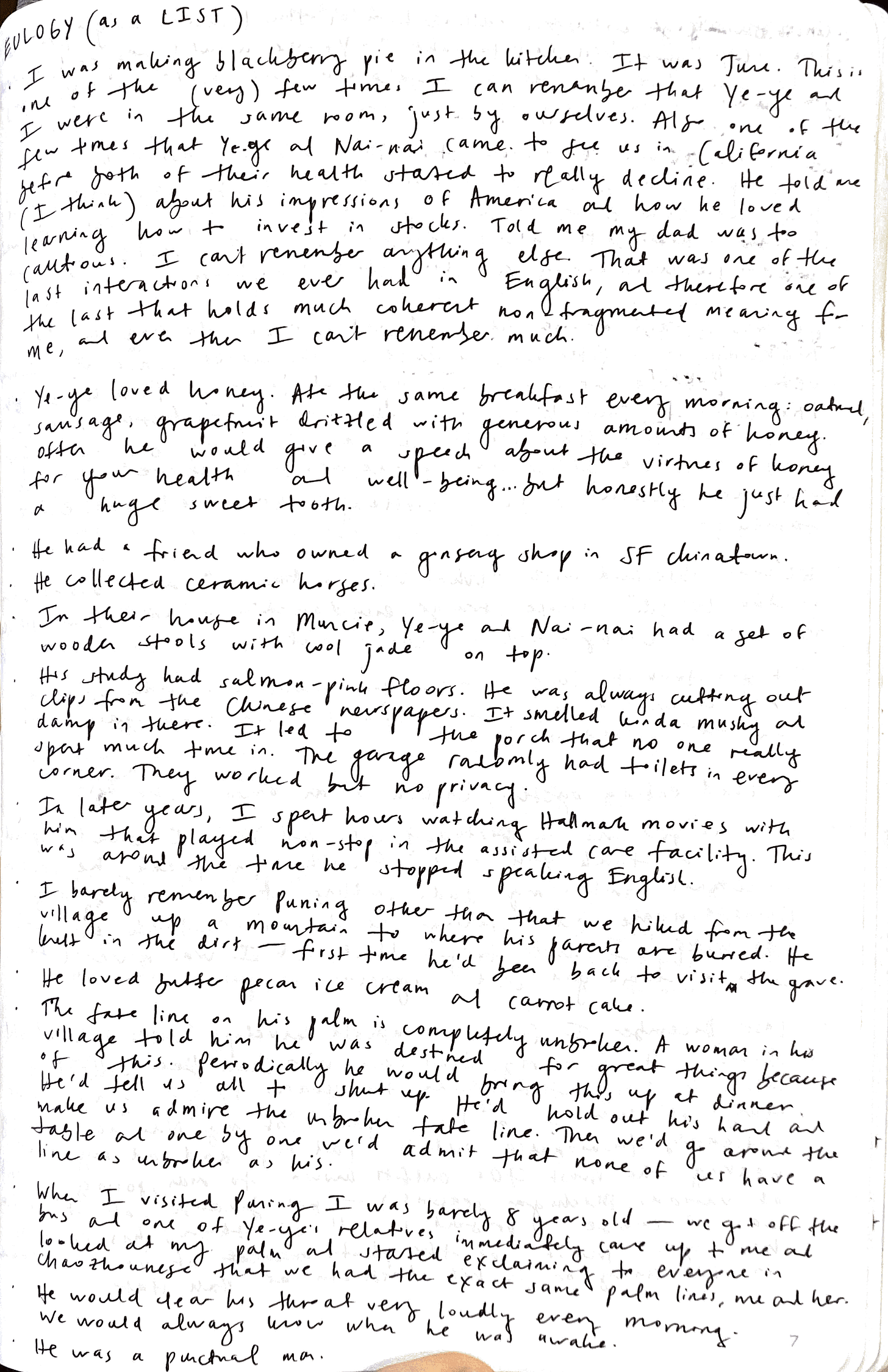

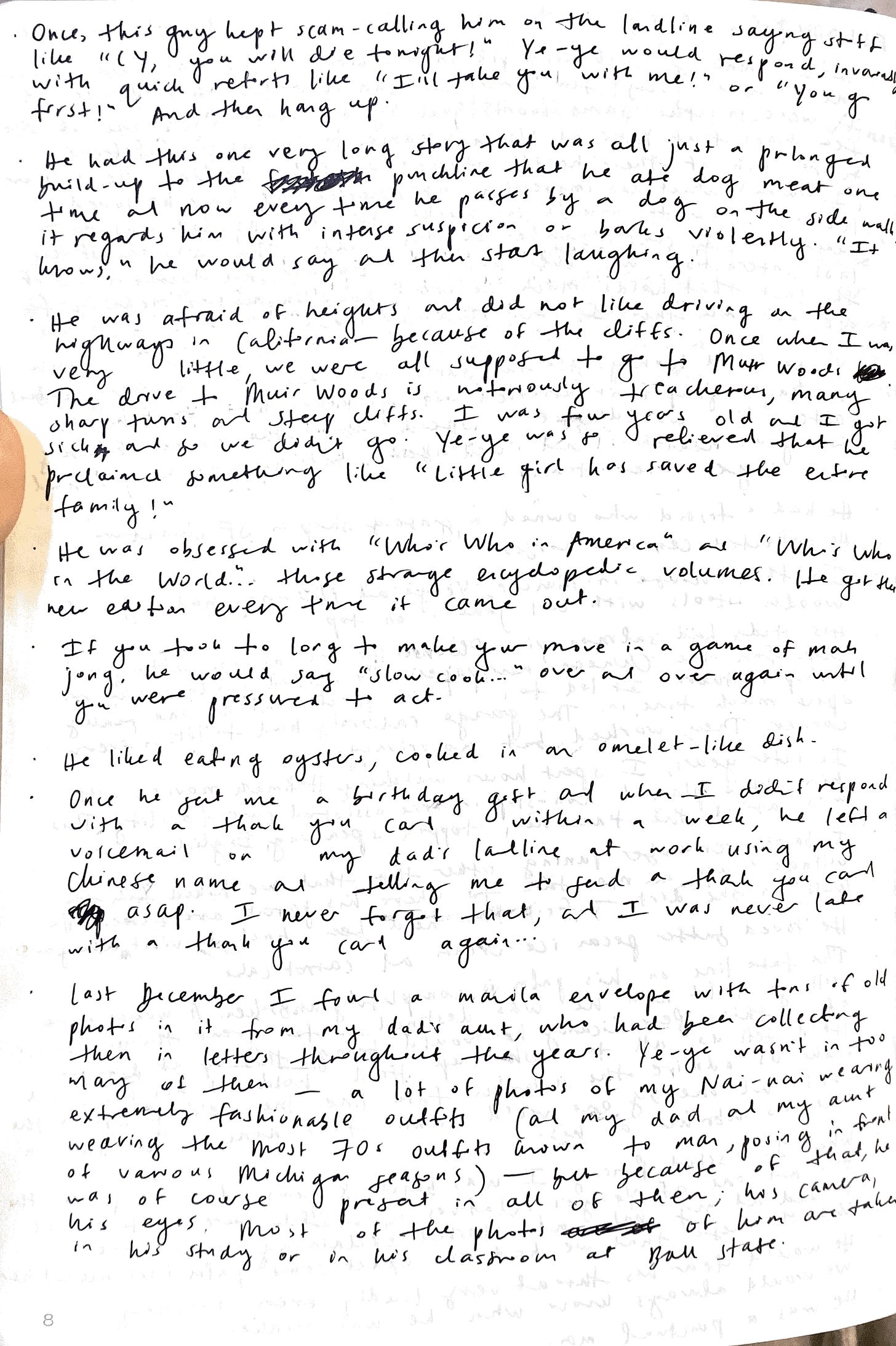

Experiment 1: Eulogy (as list)

I find a lot of comfort in lists when I can’t figure out what I’m saying. By removing the imperative of coherence, I can examine the gaps in my head more honestly. This is helpful for grief and forgetfulness in particular, a gap-ridden space.1 Here, I gave myself the simple prompt of filling two pages with things I remember of Ye-ye, with no regard for chronology or relative levels of importance.

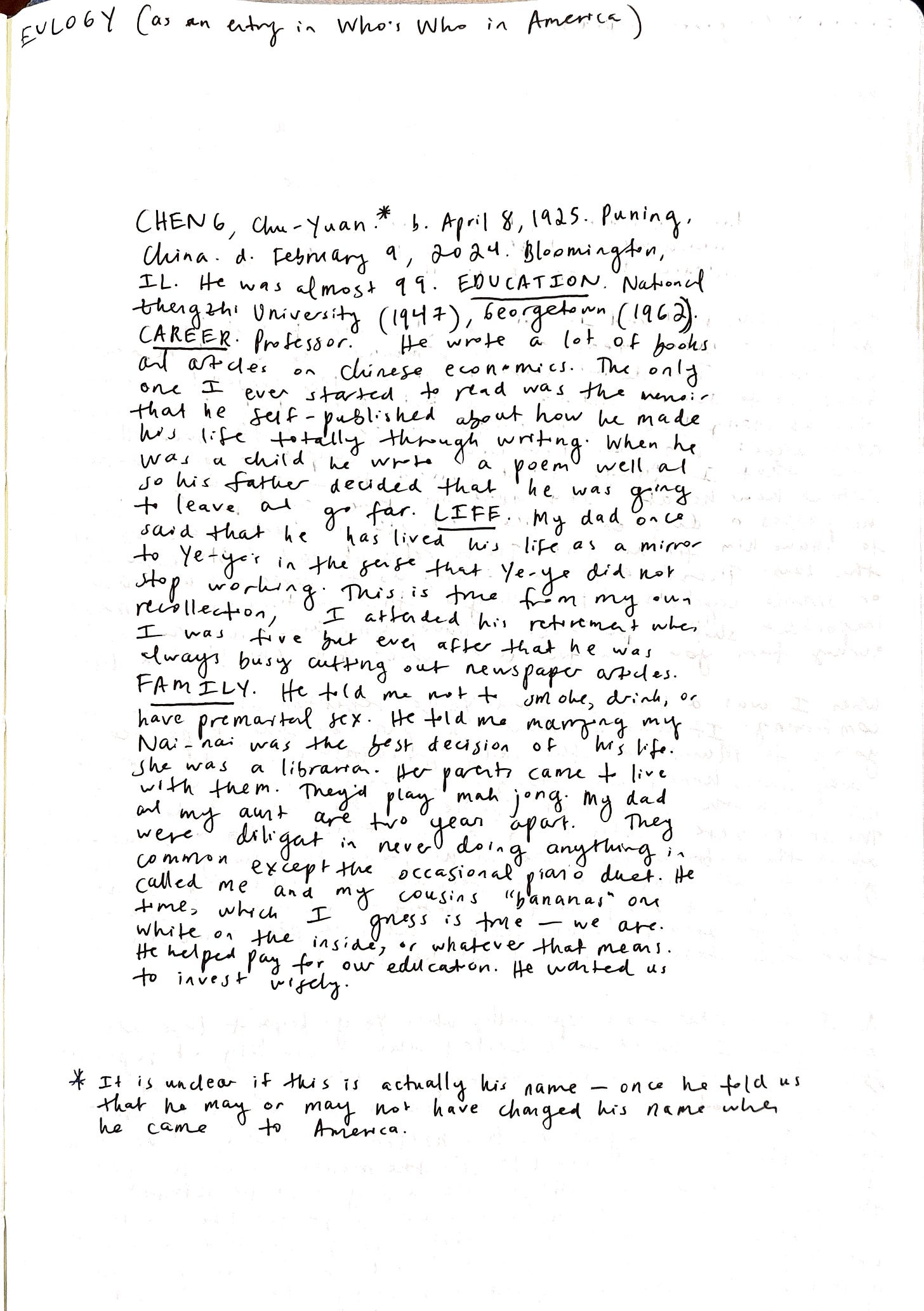

Experiment 2: Eulogy (as Who’s Who in America entry)

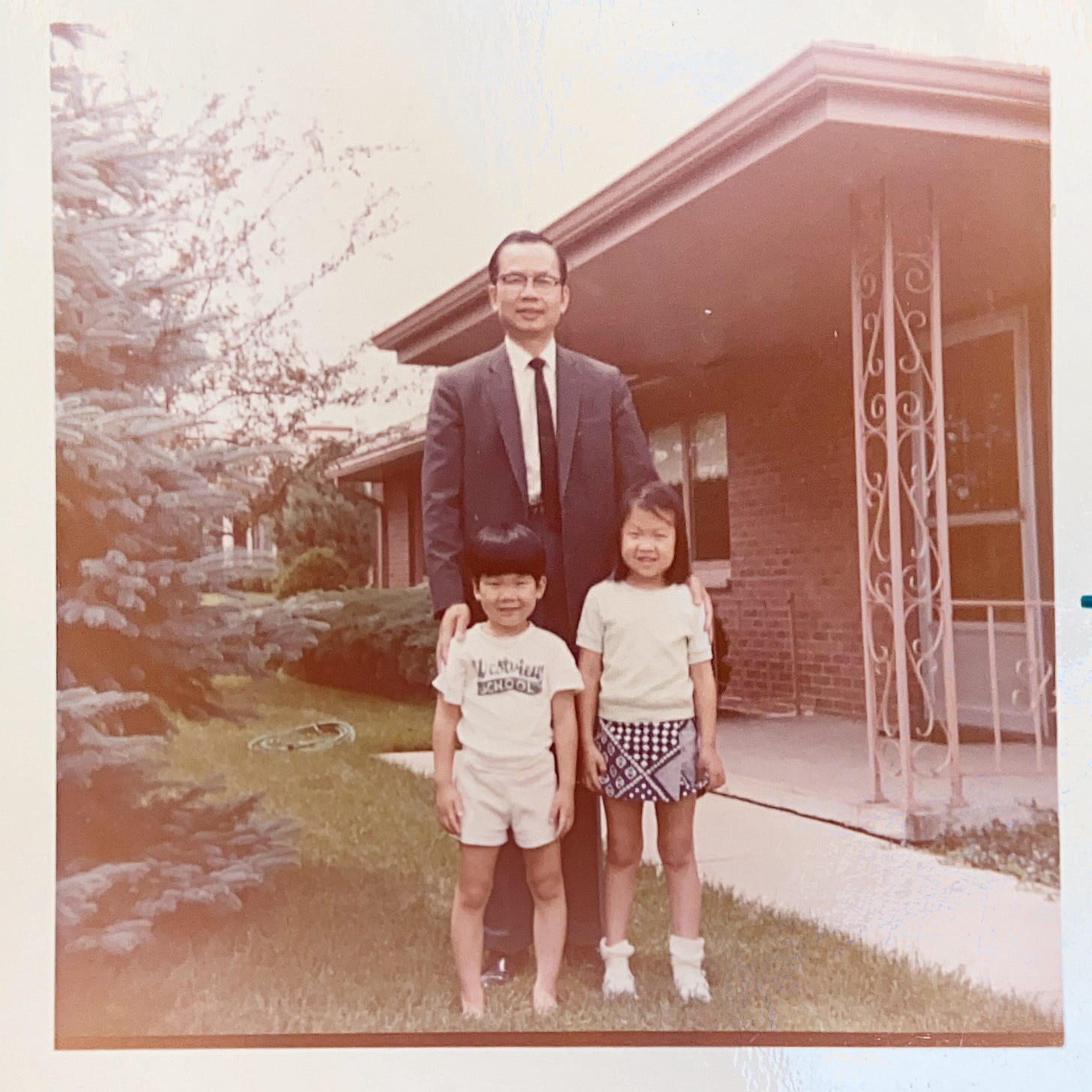

I have no idea how well-known the Who’s Who series is on a widespread level, but Ye-ye really was obsessed with these volumes. It was, uncharitably, a direct manifestation of his most self-aggrandizing impulses (we would be his captive audience as he showed off how long his Who’s Who entry was), and more charitably, a reminder of how much he cared about having made a legible American mark as an immigrant.

The Who’s Who entry, as I understand it, is kind of like an obituary for the living, which is why I found it interesting to experiment with now that Ye-ye has passed away. It contains basic biographical details—birthday, education, career trajectory, family members, current location of residence. It functions somewhat like the yellow pages but for (purportedly) notable names, although it’s a bit of a scam. In this experiment, I was interested in working within those indexical parameters and within the very notion of notability and findability.

Experiment 3: Eulogy (as “pastoral elegy”)

In Lit Hum, my professor (who specializes in 18th century poetry) gave us a series of elegies to read, from John Milton’s “Lycidas” to several poems by the contemporary poet Roger Reeves who visited our class (we read “Domestic Violence” and “The Mare of Money”). Many of these elegies, even the most contemporary ones that don’t necessarily follow the exact form, participate a poetic lineage that originated in the pastoral elegy. To simplistically condense what the pastoral elegy is: usually it’s a shepherd (or like goatherd idk) mourning the loss of his fellow shepherd and singing a song of his loss, while also (often) mourning a bunch of more abstract things, whether that be the loss of nature or the loss of a place or the loss of youth, etc.

Eulogies and elegies are extremely distinct, and sometimes even diametrically opposed. The eulogy is, literally, a speech of praise, and more specifically, a speech about the person who died that takes place within the direct context of their funeral. The elegy is often not about the person who died, even though their death is the occasion for its writing. Elegies are about what the death represents, kind of, but more pointedly, while eulogies are explicitly a process of familiarization and personalization, elegies operate within a space of estrangement and distancing. The voice is aware of how removed it is from the dead, while externally expressing its familiarity. “Lycidas” is a very clear example of this. John Milton did not know or really give much of a fuck about the dead classmate he was writing about, but the poetic voice of “Lycidas” mourns the classmate with staged (although not totally artificial) fervor in its outcry. The ethics of that are extremely fraght, of course, but what results is the strain of forced familiarity — a paradox, in other words, that aims at the contradictions of grieving.

In truth, it is still challenging at times to confront the extent to which I don’t know or understand Ye-ye. I only saw him once or twice a year. For many years, I didn’t know enough Chinese to pick up on the greater nuances of what he was saying. I forgot many of his stories because I was not paying attention. I didn’t know where in China he went to college until I read his obituary. I learned a lot from reading his obituary that I should have known before. Writing the eulogy-as-elegy was helpful for me in this way, a way of grappling with my familiarity and estrangement; in its “pastoral” premise (not countryside in a literal sense, but any “lost” place), it also helped me reflect on how many of my memories of him are also memories of places.

(Side note: Kaylee has been trying to get me to enjamb for months… “like just break ANY LINE!!”… I do not write poetry….. this is the best she’ll get for now)

Eulogy (draft)

Here is a work-in-progress draft of the eulogy I’ll be giving tomorrow.

Bonus: various random things I’ve been reading (or have revisited recently) about grief

Kitchen, Banana Yoshimoto. I loved this book… a deceptively simple read.

Notes on Grief, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. (I think part or all of this is available on the New Yorker?) I read this when it came out in 2020 or so and revisited recently.

The Rain God, Arturo Islas. Eli wrote their incredible thesis on this novel (and in particular, ecologies of the desert borderland as they relate to the Chicanx family, queerness, and grief), which I had the honor of peer-reviewing. I’m finally reading the book right now and it’s like a cleaver to the heart, especially in its depictions of grieving diasporas and chronic illness.

The Friend, Sigrid Nunez. I was not the biggest fan of this actually, but it certainly digs into the relationship between grief and writing, not in the specificity of eulogy writing but in the intervention of grief into a writer’s life.

The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion. Adding this one specifically because I really did NOT like it and have been trying for awhile to figure out why. Didion says some very universalizing things about grief that feel misplaced; but she also fails to present a singular portrait of her dead husband. Maybe the lapse of both is the point, but it felt so pretentious and unsatisfying idk.

“Ghosts,” Vauhini Vara. This is an essay I return to not only for thinking about grief, but thinking about how to engage with AI from the cautious humanistic perspective.

“Requiem,” Anna Akhmatova. Read this for the first time in Lit Hum with Prof Stewart, and then read Akhmatova’s entire poetry collection during a particularly strange week at Oxford last year, which I would also recommend, though they are incredibly bleak in the ice-cold Soviet way.

“In the City of Light,” Larry Levis. Thank you to Kaylee for gifting me this poem at the exact right moment.

I think Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Notes on Grief is a great example of this.